WHEN TO ASK FOR THE MONEY BACK…

By Peter Klugsberger

After several hours of unsuccessfully trying to tilt luck in his favor, a roulette player picked up the remainder of his bankroll and walked over to the cage to cash-out. Anxious to hit the bar for a breather, the player did not pay much attention to the transaction and grabbed the wad of money offered by the cashier. Little did he know that he was just overpaid $ 2,000.

I believe many will sympathize with me that aforementioned situation is not uncommon in our industry. The real challenge though, in my humble view, is in getting managers to agree on an objective set of criteria that would aid them in choosing whether to approach a customer for the money or not.

Clearly, this decision should not be taken lightly, in particular since it carries significant risk – including that of losing the customer’s business forever. Admittedly, many jurisdictions have clear-cut rules and procedures regarding erroneous payments and consequently don’t leave much room for managerial discretion. This holds particularly true in heavily regulated environments such as Australia or New Zealand, where letting players keep erroneous payments could result in getting the casino’s management into serious trouble with regulating authorities. Evidently, my approach in this article does not claim to apply to this particular circumstance – but let’s face it, there are no decisions to be taken.

To satisfy my own curiosity, I quizzed several of my managers and colleagues on how they would approach this problem. Evidently, I wanted them to tackle this issue from a commercial rather than an ethical perspective. Interestingly, the responses ranged from one end of extremes to the other and, in general, their choices did not seem to follow any rational decision making process that could be successfully replicated. Considering the wide range of outcomes, it became quite apparent that basing one’s decisions primarily on managerial intuition and past experience dramatically increases the risk of being inconsistent. This ad hoc approach to decision making, in turn, inevitably leads to a suboptimal customer experience, thereby dramatically increasing the risk of losing the player’s business.

The Basics

The decision making process can be broken down into several distinct components. It starts with defining one’s desired outcome – in our example, the expected result is expressed in monetary terms. Moreover, achieving the desired outcome is dependent on two additional variables: the number of available alternatives and the level of uncertainty of each event occurring. Therefore, to make decisions in the most reasonable way, we can identify the best possible choice by using the following formula:

Expected Monetary Value = Probability x Alternative

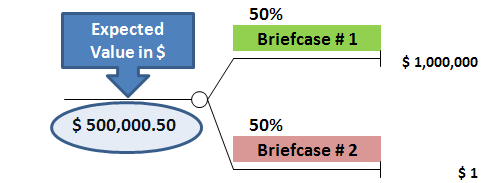

To illustrate the ease of applying this formula to a non-gaming context, television game shows offer particular fertile grounds for exploration. A lot of you will be familiar with the NBC hit game show ‘Deal or No Deal’ where a contestant is confronted with a number of sealed briefcases full of amounts of cash – varying from $ 0.01 to $ 1 million.

Let’s assume for a moment that you made it to the final round and have the alternative of choosing between the content of two sealed briefcases – one containing a prize of $ 1 and the other $ 1 million. “The Banker” calls the show’s host and extends an offer of $ 300,000 in exchange for both briefcases. Should you accept the tempting “Banker’s” offer or stick with choosing a briefcase?

Using the aforementioned formula, we can structure this problem by plugging figures into a sequential decision tree.

Evidently, the probability of choosing the ‘right’ briefcase is 50/50. To arrive at the expected value of this decision, we merely have to multiply the probability of the event occurring with the monetary value of each alternative (and add the resulting amounts). Given that the expected value of the briefcases content is significantly higher than the “Banker’s” offer, the correct decision would be not to accept it and to proceed with the contest – despite the risk of ending up with the $1 briefcase.

As this example vividly demonstrates, the clear benefit of following this logical approach is that it can protect managers from their inherent cognitive and emotional biases – errors in the way the brain processes information. It is noteworthy though, that the ‘correctness’ of the decision does not guarantee its achievement – although it will improve your chances in the long-term.

Promotional Payments & Service Empowerment Codes

A significant number of casino operators recognize the need to establish formalized procedures to promote rapid dispute resolution, thereby aiming to legitimize promotional payments to customers. These so called ‘service empowerment codes’ come in all shapes and forms, but essentially, they are intended to speed up decision-making by relegating authority down the hierarchical ladder. Although well intentioned, most of them fall into the trap of primarily focusing on the disputed amount rather than the player’s monetary value to the company. For the most part, service empowerment codes do a decent job in grind-action scenarios where there is little risk involved (i.e. low player value + small dispute amount). However, they reveal their apparent structural weakness in high-value environments. For example, one of the major shortcomings of ‘empowerment codes’ is that they do not help managers in ascertaining at what point it becomes prohibitive to give in. Promotional payments only make economical sense if they are directly related to the player’s value to the company (e.g. letting a $100 BJ player keep a $50,000 overpayment might raise questions regarding one’s business acumen). Equipping front-line manager’s with more relevant information, such as a maximum dispute amount (as a percentage of the player’s worth) could dramatically improve the success rate and lower the overall cost of these programs.

A Simple Framework

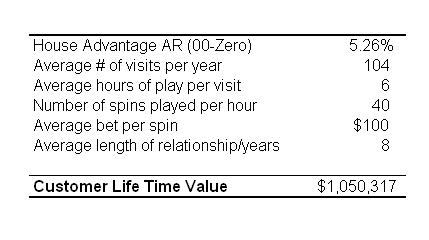

Before approaching a customer to recoup erroneous payments, a manager must first determine the level of risk involved. An easy way to do this is by ascertaining the customer’s Lifetime Value (LTV) in monetary terms – i.e. calculate the future net cash flows that a customer will generate over his/her ‘lifetime’ with the casino[1]. In our case, the player’s value can be derived by applying the theoretical win formula over the period of the relationship:

The calculation of LTV can be conducted in a mere ‘back of envelope’ fashion, thereby rapidly eliciting clues on the importance of the customer’s business to the casino –without worrying too much about nickels and dimes. The company’s risk exposure can then be established by contrasting the amount to be recouped with the overall customer value. The rule of thumb is: the bigger the disparity between the overpayment and the customer’s LTV, the higher the risk to the company’s bottom line – and potentially to the manager’s career. Conversely, the smaller the gap between these amounts, the lower the importance on ‘getting it right’.

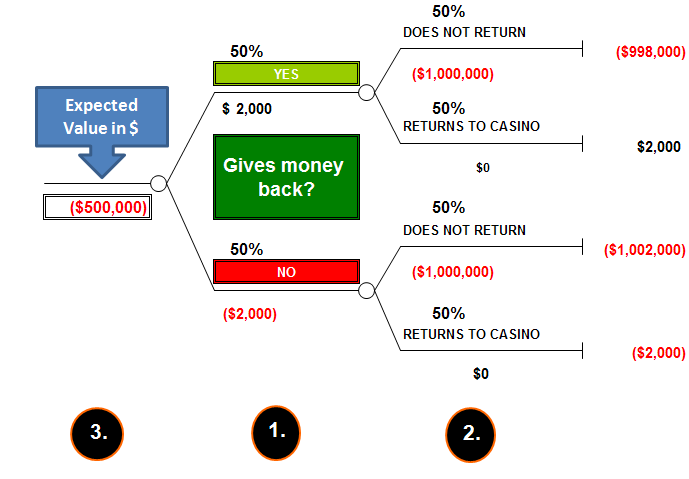

Equipped with these essential numbers on the customer’s LTV and the amount to recoup, the manager sets out to plug this figures into a basic decision tree in Microsoft Excel.

In the first step (1), we consider if the customer will either give the money back to us or not. For the sake of simplicity, I assumed the probability of this event occurring to be 50/50. So the financial impact up to this point would be the casino recouping the money (+$ 2,000) or not (-$ 2,000). Clearly, the probabilities can be adapted to fit the specific context of the situation.

In the second step (2), we deal with the fact that – after having been approached by our manager – the customer might get upset and decide not to return to the casino. In this scenario, we would stand to loose any future net cash flows. Conversely, there is no positive or negative financial impact if the customer returns to the casino as if the incident never happened – the casino would not generate ‘additional’ revenues and therefore the value of this decision is negligible ($ 0).

In the final step, the validity of the decision to either approach the customer or not can be elicited by simply looking at the expected outcome in $ (3) – if the amount is negative, than the manager should not approach and vice versa. The attractiveness in this approach is that you are taking the commercially ‘right’ decision with a long-term view. In the short-term, a persuasive manager might be able to succeed in some instances to recoup the money (and keep the player for that matter). However, this ‘we have to make an attempt’ approach is inherently flawed and will not produce desired results in the long-term.

After training my entire management team in this approach, one of them was still not convinced and he assured me that he could beat the odds and recoup any amount without losing the customer – I ended up leaving it up to his discretion on how he wanted to proceed. Nonetheless, I reminded him that if one of his attempts goes awry, he will end up in the CEO’s corner office. I could not help wondering which scenario he would prefer to be in – explaining to the CEO why he did not get the $ 2,000 back or how he lost a million dollar customer. I know which position I’d rather be in…..

Peter Klugsberger has worked in the gaming industry for nearly two decades for one of the largest international gaming operators. His past assignments have involved stints in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Slovakia, Switzerland, and Venezuela. Peter holds a Global Executive MBA from the IESE Business School. You can reach Peter at pklugs@yahoo.com.

[1] Some assumptions are based on Lisa Watson & Sudhir H. Kale’s Article “Know When to Hold Them: Applying the Customer Lifetime Value Concept to Casino Table Gaming.”